The Story of Boehm and Otterbein

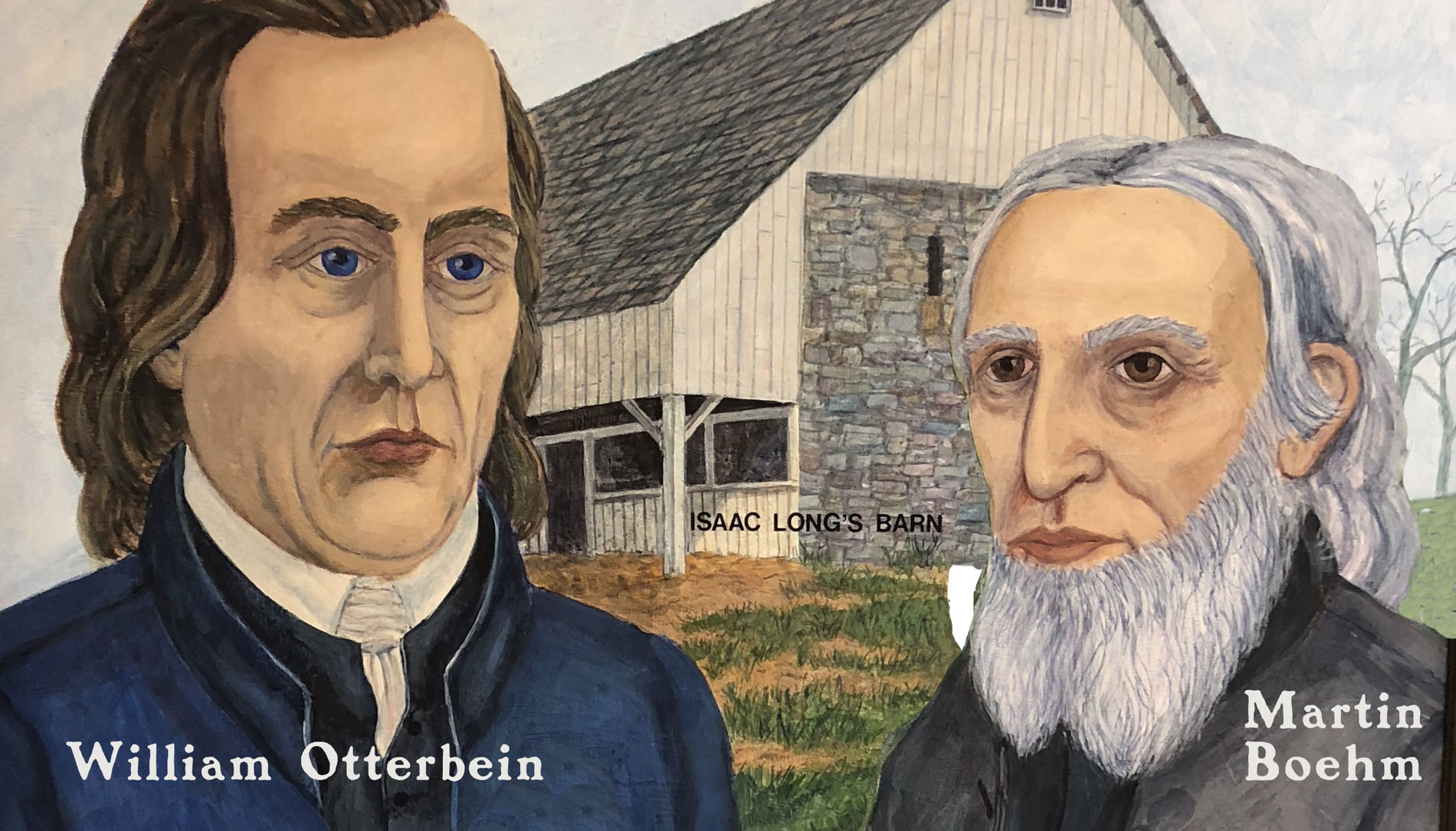

In 1967, people from across the denomination met in Lancaster, Pa., to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the United Brethren church. A gathering was held in Long’s Barn, where it all began with an embrace between William Otterbein and Martin Boehm. Those men, our founding fathers, hadn’t met until that day in 1767.

The anniversary 200 years later included a re-enactment of that embrace. A young UB pastor in Pennsylvania named Ray A. Seilhamer, who went on to serve as bishop 1993-2001, played the part of Martin Boehm. Raymond Waldfogel, an Ohio pastor who would serve as a bishop 1969-1981, took the part of William Otterbein. It was good casting.

On September 25, 2000, we celebrated another 200th anniversary. On that date in 1800, a group of ministers met in Frederick, Maryland, and took two significant actions: they elected the first bishops (Otterbein and Boehm), and they chose a name for the movement which had spread through Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia for 33 years. They called it the Church of the United Brethren in Christ.

“As the head of a family, a father, a neighbor, a friend, a companion, the prominent feature of his character was goodness; you felt that he was good. His mind was strong, and well stored with the learning necessary for one whose aim is to preach Christ with apostolic zeal and simplicity.” –Francis Asbury, speaking about Martin Boehm

Martin Boehm was born in 1725 just south of Lancaster, Pa. He was the son of a Dutchman, and the grandson of a Swiss who had become a Mennonite while working in Germany (did you get all of that?). He married a Swiss immigrant, Eve. Four of their children died as children. The only surviving child, Henry, spent 64 years as a Methodist minister, part of it as a traveling companion of famed Methodist bishop Francis Asbury, and died six months after turning 100.

Martin Boehm became a minister in 1756 at the Mennonite church in Byerland, Pa. But it wasn’t the usual path to the ministry. In those days, when a church needed a new pastor, persons from the congregation were nominated for the position, and each nominee selected one of the Bibles standing before them. Only one Bible contained a slip of paper with Proverbs 16:33 written on it: “The lot is cast into the lap, but the whole disposing thereof is of the Lord.” Boehm chose that Bible, and presto!, he was a pastor.

Boehm lacked confidence in his preaching skills. Indeed, it was written that he would “stammer out a few words and then be obligated to sit down in shame and remorse.” He agonized over this for months, and after much prayer, came to the realization that he wasn’t even, truly, a Christian. One day as he plowed his fields, he knelt at the end of each row to pray, and the word “Lost, lost” continually hovered over him. Finally, halfway through the row, he broke. Falling to his knees, he cried out, “Lord save, I am lost!” The verse immediately came to him, “I am come to seek and to save that which is lost.”

Boehm wrote, “In a moment, a stream of joy was poured over me. I praised the Lord and left the field.”

And from that day, preaching became a joy—a passion—and he zealously spread the message of salvation to which he had been oblivious for so long. He wrote, “This caused considerable commotion in our church, as well as among the people generally. It was all new.” Lives were transformed. The Great Awakening had come to the Mennonites.

Five years later, when the Mennonite bishop died, Boehm was chosen—again, by lot—as the new bishop. At age 36. In that role, he participated in Great Meetings, as they were called—three-day events attended by several hundred people, sometimes held in barns, in orchards, or outside. Whole communities would find the Holy Spirit descending in power and changing everything.

The Great Meeting we know most about occurred on May 10, 1767, at Long’s Barn in Lancaster, Pa. Bishop Boehm spoke in the barn while some of his Mennonite pastors preached in the orchard outside. Boehm told of his plow-side conversion. As the sermon ended, a Reformed minister named William Otterbein rose from his seat, hugged Boehm, and declared, “We are brethren.” Our denomination’s name is based on Otterbein’s impromptu words.